Here's a preview from my zine, The Secret Rules of the Terminal! If you want to see more comics like this, sign up for my saturday comics newsletter or browse more comics!

get the zine!

get the zine!

read the transcript!

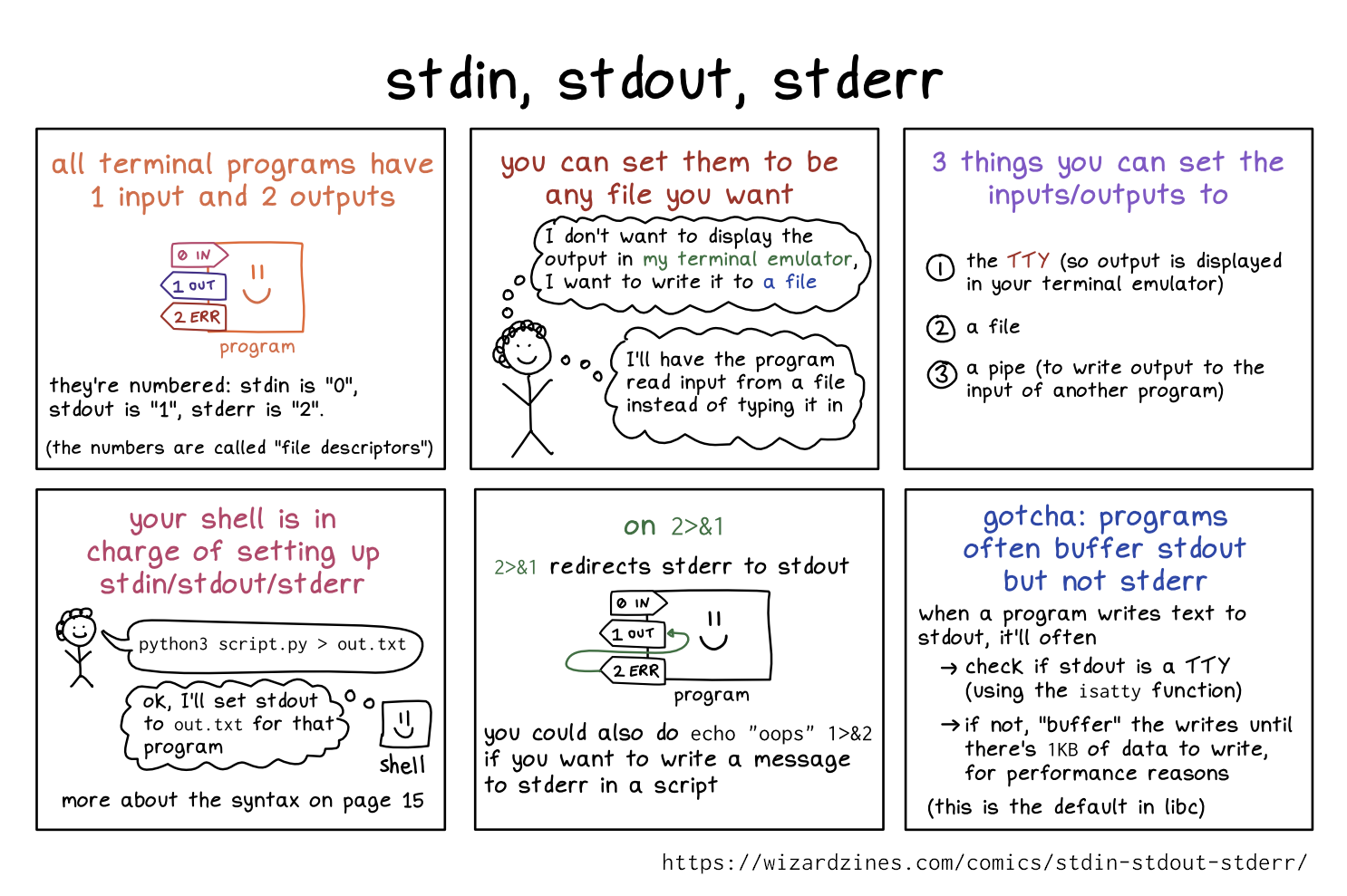

all terminal programs have 1 input and 2 outputs

they’re numbered: stdin is “0”, stdout is “1”, stderr is “2”.

Illustration of a program, represented by a box with a smiley face. There is an arrow labelled “0 IN” going into it, and arrows labelled “1 OUT” and “2 ERR” coming out of it.

(the numbers are called “file descriptors”)

you can set them to be any file you want

smiling stick figure with curly hair, thinking:

“I don’t want to display the output in my terminal emulator, I want to write it to a file”

“I’ll have the proram read input from a file instead of typing it in"

3 things you can set the inputs/outputs to

- the TTY (so output is displayed in your terminal emulator)

- a file

- a pipe (to write output to the input of another program)

your shell is in charge of setting up stdin/stdout/stderr

tiny smiling tick figure: “python3 script.py > out.txt”

shell: “ok, I’ll set stdout to out.txt for that program”

more about the syntax on page 15

on 2>&1

2>&1 redirects stderr to stdout

The same illustration from the first panel, but with the addition of an arrow coming out from “2 ERR” and going into “1 OUT”.

you could also do echo "oops" 1>&2if you want to write a message to stderr in a script.

gotcha: programs often buffer stdout but not stderr

when a program writes text to stdout, it’ll often

- check if stdout is a TTY (using the

isattyfunction) - if not, “buffer” the writes until there’s

1KBof data to write, for performance reasons

(this is the default in libc)